Honoring Black Heroes

Recognizing Black History: Black People Who Changed The Course of Modern Agriculture.

Franklinton Farms operates the land with intention and bases its best practices on those passed down from generation to generation of oppressed communities who farmed brilliantly.

We need to start by saying that our respect for the land includes the Indigenous peoples who stewarded this Place long before us. We acknowledge our land as the historic and modern territory of the Delaware, Shawnee, Mingo, Ojibwe, Peoria, Potawatomi, Wyandotte, Miami, Cherokee, and Seneca peoples.

We also acknowledge the oppressive history of agriculture in this country that includes enslavement of Black peoples for several hundred years, disrupting any sense of the proper cost of farmed goods, and establishing white peoples’ ownership of land and capital. We are all still benefiting from agricultural knowledge that arrived with the enslaved peoples.

Finally, we readily acknowledge that some of our Farm Gardens used to be homes for Franklinton families that became vacant lots.

We reckon with all of these critical histories as we farm, and hope our presence on the land honors the lives of the many people who have come before us.

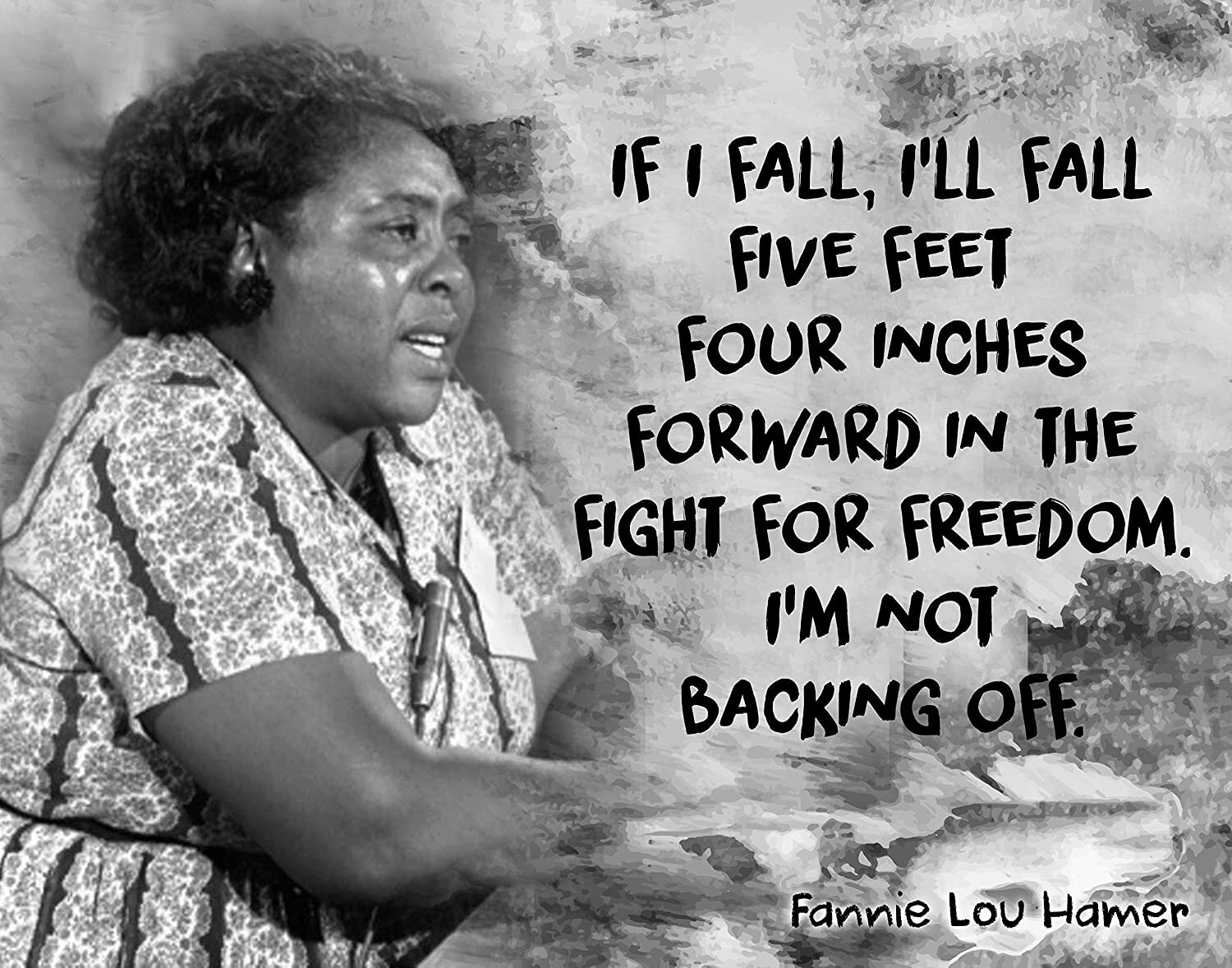

Creator of the Farming Co-op - Fannie Lou Hamer

Fannie Lou Hamer was born in 1917 in Mississippi and was an energetic and passionate activist all of her life. She fought for the right for Black people to vote, and helped register hundreds of voters.

When she saw how white people fought back by taking Black people’s land as well as denying food and financial opportunity to voters, she created a solution: the Freedom Farm Cooperative. A community-based, rural and economic development project.

The first of its kind in America.

With a grant of $10,000 from a charitable organization in Wisconsin in 1969, she bought 40 acres of Mississippi Delta land. Families could join the co-op for the small amount of $1 a month, often still too much for many Black families, but 30 signed up in the first year.

“The time has come now when we are going to have to get what we need ourselves. We may get a little help, here and there, but in the main we’re going to have to do it ourselves.”

Cash crops such as soy bean and cotton were grown in order to pay for taxes and administrative expenses. The rest of the land was dedicated to growing food - cumbers, peas, beans, squash, and collard greens - all of which was distributed back to those who worked on the co-op.

The purpose of the co-op was to provide food, but also to empower individuals and families that they could take back some control into their lives through growing their own food. It provided an access to land that was denied them through nefarious means intended to force them into sharecropping or leaving the south altogether.

The Freedom Farm Cooperative grew over the next few years and included The Pig Project, providing a source of protein to families who could not afford the cost of meat.

Hamer sought contributions from the National Council of Negro Women to start the Sunflower Pig Bank. Families could receive a piglet to raise and breed as a source of income and would then donate offspring back to the co-op, or to other Black families in need.

By 1969, the pig bank had provided over a hundred families with pigs, each of which produced over 150 pounds of meat.

“There’s nothing better than get up in the morning and have…a huge slice of ham and a couple of biscuits and some butter. . . I wouldn’t take nothing for our golden pigs.”

From there until 1976, the Freedom Farm Cooperative expanded to include

community gardens

a commercial kitchen

a Head Start program

a job training center

a tool bank

and several income-generating enterprises, such as

a garment factory

sewing cooperative

We’ve all seen these style programs gain in popularity in cities all over the world in the last two decades, often led by white people or white-led organizations. But the history lies in the efforts of Black people and their leaders such as Fannie Lou Hamer.

This radical experience constituted an important chapter in the Black Freedom Movement.

Hamer’s life and work suggests how intertwined the strategy of raising food was with the mainstream of the Civil Rights Movement of the 1960s.

This also suggests why it may be a key strategy in addressing inequality in America today.

Donate today to a QBPOC-led co-op that is looking to empower young Black folx through community, land, and food: CoFED Coop

Donate securely here:

Further Video Info:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=agBzy3ATja0

Articles Sources:

https://www.bread.org/blog/fannie-lou-hamer-pioneer-food-justice-0

https://lifeandthyme.com/commentary/fannie-lou-hamer-and-farming-as-activism/

https://snccdigital.org/events/fannie-lou-hamer-founds-freedom-farm-cooperative/